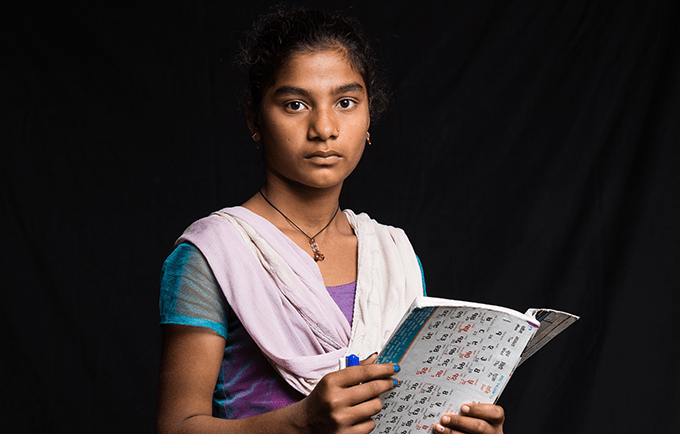

UNITED NATIONS/KAPILVASTU/ERBIL – “I’ve been married for five years – since I was 12 – but I haven’t gone to live with my husband yet,” said Rupali Kurmi, from Kapilvastu district, in Nepal. “That’s happening in about three weeks’ time.”

This Valentine’s Day, for its annual #IDONT campaign, UNFPA is partnering with artists to raise awareness about child marriage, which ensnares tens of thousands of girls around the world every single day. If nothing is done to stop these human rights violations, an estimated 70 million girls will be married, while still children, over the next five years.

These girls have no choice over whether or when to marry – or to whom. They are typically pulled out of school, and are often forced into motherhood before they are emotionally or physically ready.

“I was so young when we were first engaged, and now I have to go and live with a completely new family, even though I’ve never met them before,” Rupali said. “I haven’t told my parents this, but I’m very, very scared.”

I don’t want flowers; I want a future

Acclaimed photographer Vincent Tremeau visited UNFPA programmes in Nepal and Iraq, where girls face a heightened risk of child marriage. He asked these children to dream of the future they want, and to create costumes depicting that future.

In rural Nepal, poverty and gender inequality mean that girls are often married off before their 18th birthdays. But dozens of girls showed up dressed as doctors, civil engineers, teachers, dancers, accountants and more – a testament to what they can achieve if they are allowed to fulfil their potential.

“I’m going to own a shop that sells nothing but noodles,” said 14-year-old Maya. “There will be queues of people out the door, and nobody will ever complain about any of our products – service with a smile will be my motto.”

In Iraqi displacement camps, Mr. Tremeau met child survivors of the bloody conflicts in both Iraq and Syria. They, too, had big dreams.

“I love making things the most, so when I grow up I’m going to crochet and sew things all the time,” said Nufa, 12, from Abali, Iraq. Others came dressed as actors, sailors, artists or engineers.

The images were collected under the theme “This Valentine’s Day, I don’t want flowers. I want a future.” They are the latest instalment of Mr. Tremeau’s ongoing photo series One Day I Will.

“I felt my heart fall out”

All of the young participants were aware of child marriage – and some had seen its worst consequences.

“My best friend was married at 16, and died while she was giving birth the year after,” explained 18-year-old Sirjana, in Nepal, who wants to be a social worker. “We’d grown up together, and she didn’t want to get married – but she didn’t have a choice. When her father told me that she’d died, I felt my heart fall out.”

Globally, complications of pregnancy are the second leading killer of girls aged 15-19. And in developing countries, nine out of 10 births to adolescent girls take place within a marriage or union.

In Nepal, more than 48 per cent of adult women report that they were married before reaching age 18. And in Iraq, more than a fifth of girls aged 15 to 19 are married, according to 2011 data. Conflict and displacement could be making things worse.

For one girl’s family, child marriage seemed to be just one of several terrible choices.

Malak, 11, endured life under the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also known as ISIS or Daesh). “My sisters were 13 and 14, but my father said that they had to get married because otherwise they risked being taken by Daesh and forced to marry their soldiers instead,” Malak said. “They didn’t believe him, but it turned out that he was right: The day after the wedding, Daesh turned up at the house and beat our father as punishment.”

Know your rights

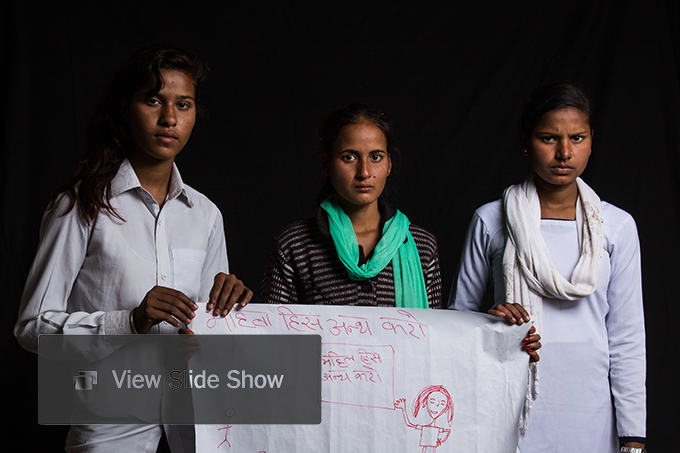

But in many cases, practical measures can help girls escape child marriage. Empowering girls to know and advocate for their rights is a critical first step.

Heba, 11, learned about her rights from a UNFPA-supported programme in her Iraqi displacement camp. "I see sometimes here in the camp the parents of some girls talking about marriage and some of them want to do it, but I always tell them that it’s a bad thing for them,” she said.

Fourteen-year-old Punita, in Nepal, learned about the harms of child marriage from a programme supported by UNFPA and the United Kingdom's Department for International Development. She wants to break the cycle by staying in school and becoming a teacher. “All of my sisters had to leave school by year seven to get married," she said, "so I’m determined to keep studying for as long as possible and get a great job – just to show the world that one of us could do it.”

Child marriage: Not a good look

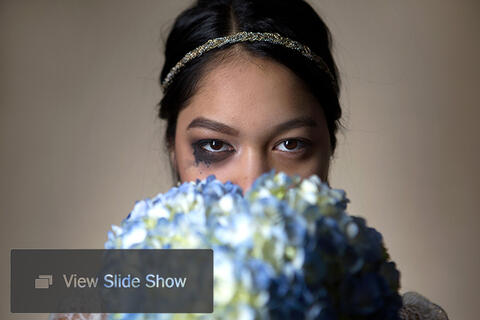

In a separate project, Palestinian artist Rand Jarallah used makeup to spread the word about child marriage. Five school-aged girls in New York volunteered to act as a canvas for Ms. Jarallah, a UNFPA Innovation Fellow.

Ms. Jarallah applied deliberately excessive cosmetics to the volunteers, who were dressed in wedding attire.

The project is meant to emphasize that marriage is not a good look on a girl.

Reporting by Corinne Redfern, Mohamed Megahed and Santosh Chhetri